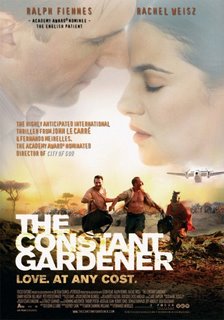

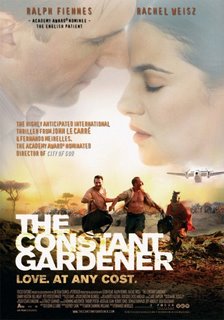

Harrowing humanity. In director Fernando Meirelles's (

City of God) second full-length film, his first in English, he works with screenwriter Jeffrey Caine in adapting John Le Carré's novel with an outstanding cast including Ralph Feinnes and Rachel Weisz (who won an Academy Award for her performance) in the leading roles. The story, a basic espionage thriller plotline, is actually engrossing.

Told simultaneously in realtime and flashback, Justin Quale (Fiennes) is a low-level British diplomat who has been given a new assignment in Kenya. His wife, Tessa (Weisz), is an activist with a keen interest in issues of poverty and social justice; Justin urges her to avoid getting too deeply involved in the people living in Kenya, who are constantly dogged by poverty, but she shows little interest in obeying these instructions. One day, Tessa disappears, and is soon found dead; officials believe that she was murdered by her close colleague, a doctor that had been working with Tessa in investigating a potential pharmaceutical scandal, after an alleged argument. However, before long Justin becomes convinced that there was a larger scheme that led to Tessa's death, and begins digging into areas where he's not especially welcome: in a distressingly convincing corrupt world where everyone is guilty and no one is responsible..

The film starts out comparatively sedate, with Justin reacting with ineffectual calm to his wife's death, even consoling his friend Sandy (Danny Huston) when he gets distressed while identifying the body. Appropriately, the film comes alive in the flashbacks to Tessa's life, and as she traverses the teeming city of Nairobi, the screen pulsates with color and the energy of cinematographer César Charlone's street-level handheld camera work. Fiennes delivers a perfectly modulated performance. Justin is a passive, ineffectual minor diplomat who marries a beautiful younger woman he doesn't really know. "You could learn me," she tells him, and over the course of the film, it becomes clear that Justin is more concerned with understanding his murdered wife than with avenging her death. This may frustrate audiences accustomed to catharsis, but it's the only way to treat the material truthfully. a distressingly convincing corrupt world where everyone is guilty and no one is responsible.

The Constant Gardener offers a superb, thoughtful, and finally heart-wrenching example of the conflation of the personal and the political.

4 out of 5 stars